The Battle of Bunker Hill. Tuesday, June 17, 2025.

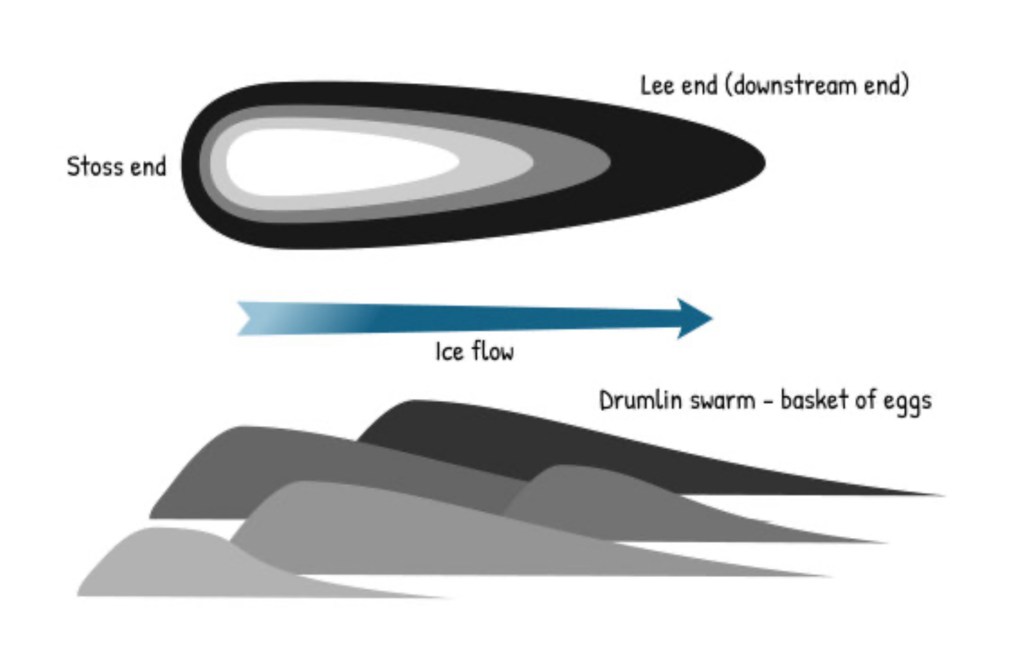

It’s time I fessed up, I have a drumlin fetish. Having spent my wonder years in Boston, I became obsessed with these little glacial hills that dotted the landscape. You’ve heard of some of them: Beacon Hill, Bunker Hill, Winter Hill, Mission Hill, and most of the islands in Boston Harbor. They have a typical shape: about a mile long, oval, around 100 feet high, steeper on one side, typically pointing southeast, often occur in “swarms”.

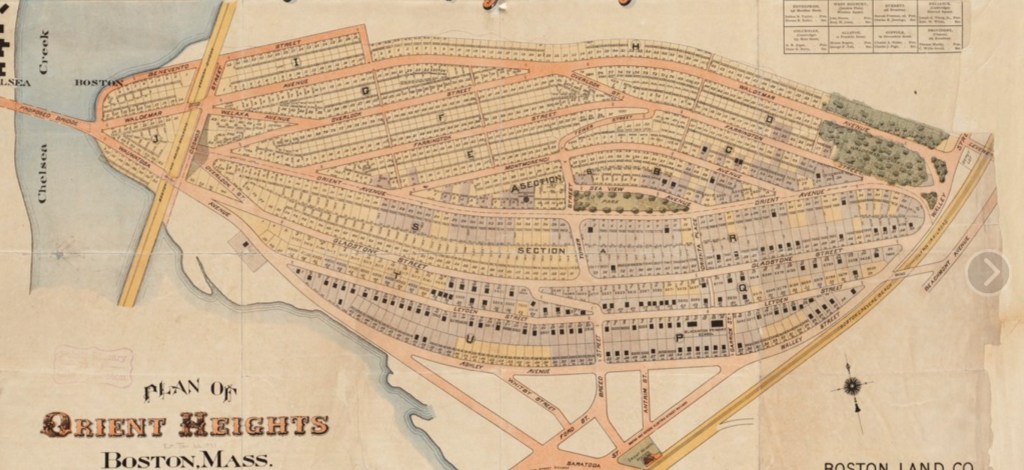

Most of the ones in Boston have been adulterated, carved up by development, the top 50 feet of Beacon Hill was dumped into the harbor for landfill. Orient Heights in East Boston, just north of the airport, is a textbook drumlin, but darned if I could find a picture of it on the web, just this map from 1894.

Great Brewster Island in the harbor is another classic drumlin.

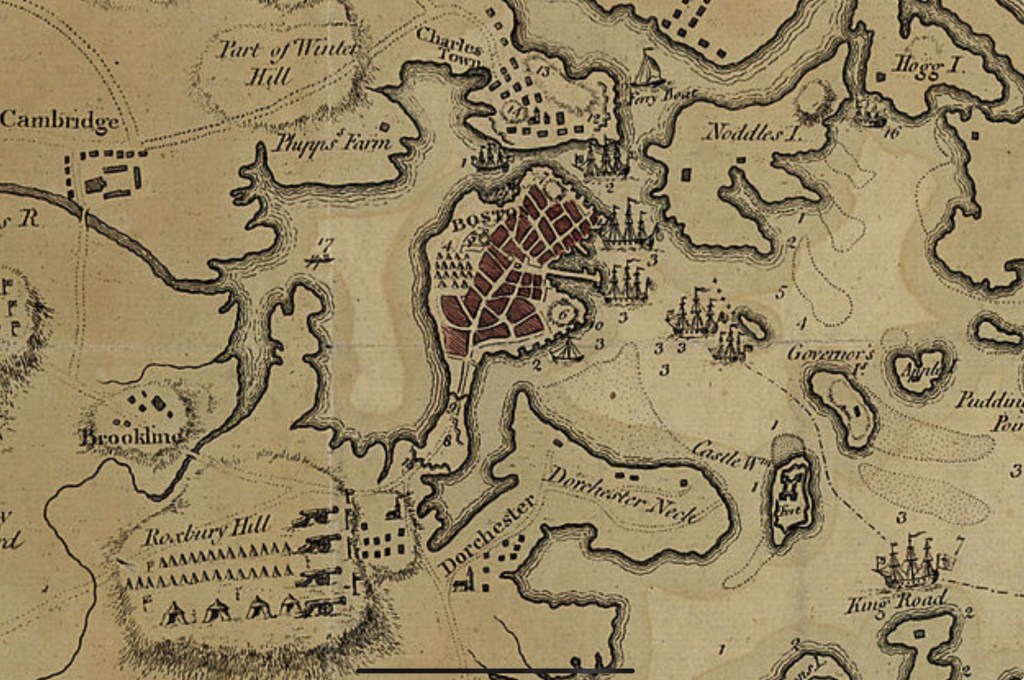

These little hills played an outsized role in the birth of our nation. Seizing the high ground, even ground as low as these, confers enormous strategic advantage. After the debacle of Lexington and Concord, British soldiers and loyalists were basically under siege, holed up in Boston, which then was almost an island, connected by a thin neck with a single road, surrounded by tens of thousands of hostile provincials. Their only lifeline was the sea, but that one was a doozy, the British Navy was unsurpassed in the world.

The British commanders realized that the closest hills, in Charlestown and on Dorchester Neck, represented a serious threat if occupied by the colonials. The night before the Redcoats planned to secure them, the provincials, tipped off by spies, worked all night to dig a crude earthwork on Breed’s Hill, #14 on the map. Sunrise on the morning of June 17, 1775 revealed to the outraged commanders that their plans had been co-opted, and the shelling started immediately. Most of the British guns couldn’t aim that high, and colonial fortifications continued. It took until 3 PM to land Redcoats in Charlestown, and march up the hill. It must’ve been a terrifying site to see. The rebels, low on ammunition, held their fire until they could see “the whites of their eyes”, but then unleashed devastating volleys. The British had to fall back, regroup, and try an additional two times before prevailing against the provincials who had completely run out of ammunition. The heroic Joseph Warren, whose spies had proved so crucial, was killed in that final assault. When the dust cleared on this first pitched battle of the Revolution, the British had “won:” they had seized Breed’s and Bunker hills, but at a cost of 1000 casualties, twice as many as the other side. General Howe, the new commander, deemed it “a prize too dearly won,” The rebels wished they “could sell them another hill at the same price.”

The other hill, obviously, was the one on Dorchester Neck, but Howe, perhaps chagrined by the earlier experience, dragged his feet about taking it. Meantime, the Second Continental Congress had appointed George Washington as commander of the newly formed continental army, and he arrived a month later to assume the ongoing siege. They decided a direct attack on Boston was too risky, but didn’t have artillery to secure the drumlin on the neck (now known as Telegraph Hill in South Boston.)

Enter three American heroes: Ethan Allen, leader of Vermont’s boozy Green Mountain boys, Benedict Arnold, a competent commander who had not yet turned traitor, and Henry Knox, a Boston bookseller. Allen and Arnold had captured Fort Ticonderoga, the “Gibraltar of the continent,” without firing a shot on May 10. Legend has it that Ethan woke the sleeping commander and demanded “surrender in the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress” but knowing Ethan, he likely said something more profane. Whatever, the stunning victory had netted the Americans some significant ordinance. Tasked with transporting the guns to Boston, Knox conducted the celebrated “noble train of artillery” over 300 miles unforgiving winter topography using oxen, sleds, boats, and sheer manpower.

By early March 1776, Washington had his ducks (or guns) in a row. In a hidden nighttime operation that rivaled what the provincials had done the year before on Breed’s hill, he fortified the Dorchester drumlin. Howe woke the morning of March 4 with déjà vu all over again, I love to picture him saying “D’oh!” Once again he launched an expedition to dislodge them, but a late winter storm kept him from landing, and each day, Washington strengthened his position. All of Boston Harbor was under his guns. Finally the British realized they had no choice but to leave. On St. Patrick’s Day, 1776, still celebrated in Boston as Evacuation Day, Washington entered the abandoned city, having won his first victory without firing a shot.

There are themes here: nighttime operations, sometimes bloodless battles, but to me, the liberation of Boston was all about the drumlins.

You know me, I couldn’t leave it at that. I “reenacted” the Battle of Bunker (really Breed’s) Hill by bike last month, not quite on the semiquincentennial. I knew better than to show up on the actual day. Every year, Charlestown celebrates Bunker Hill Day with a massive parade that circles the entire peninsula, traditionally attended by every politician in the state. One year I was trapped inside and couldn’t leave for hours. Today’s parade, I’m sure, will top them all.

The ride was low-key by my grandiose standards, just from my sister‘s place in Newton to the battlefield and back, stopping by Copp’s Hill (another drumlin) where the Old North Church is, the USS Constitution, and noting that, even at 73 feet, Breed’s Hill is a steep little sucker.

Kind of comical, really, the monument is three times as tall as the hill is high. I’ve been there before, but the tower was always closed. This time it was open, a chance to climb 294 spiral steps, getting more claustrophobic as the tower narrowed towards the top, and peek out the tiny windows. At the base, there used to be a terrific multimedia exhibit The Whites of Their Eyes, but that was a bicentennial project that closed years ago.

Returned via my favorite Cambridge bike shop, then got to bed early for my annual Cape Cod bike ride. The subject of my next post.

Distance 27.4 miles, time six hours. Elevation gain 752 feet.

©️ 2025 Scott Luria