Random musings on Cape Cod. Saturday, July 26, 2025.

When most people in the US talk of the Cape, they mean Cape Cod. Certainly in the eastern US. It’s one of the most prominent features of the country’s outline, after Florida and the Great Lakes.

The distinctive silhouette is etched in the national consciousness, echoed in other iconic images

Most compelling of all is the smooth sweep of the Outer Cape, culminating in the fist, the spiral that is Provincetown.

It was my great fortune to have lived and worked in Provincetown for three years in the 80s, in the early years of the AIDS epidemic, paying back my commitment to the Public Health Service, which put me through medical school. A magic time: the people, the beaches, the lobsters, the oysters, the art— all suffused with that special light that comes from being surrounded by water.

A “cape” is also a distinctive house, available in a selection of sizes, with or without dormers

I’m not a fan of EZ-listening music, used to call it “slush pump music”, but who can resist the smooth stylings of Patti Page’s classic Old Cape Cod? https://youtu.be/a34kIKVideI?si=Br5MCPbBqBrgXSnw

So yeah, the Cape has a grip on our national psyche. But how did this peculiar feature of geography come to be? While living there I hit the books (no internet back then), explored the National Seashore, talked with rangers, and hired a colorful local field botanist, Richard LeBlond, a middle-aged hippie who seemed to know more about the geology of the Cape than anybody, for many hours of walking tours.

It all started with our friends the glaciers, who gave us the drumlins of the last post. In the last Ice Age, about 20,000 years ago, the Laurentide ice sheet extended down past southern New England. Sea level was many hundreds of feet lower than today, the water tied up in the polar ice caps, so that what are now Massachusetts and Cape Cod Bays were dry land. As the planet warmed and the glaciers retreated, they left piles of rubble at their terminal and lateral edges called moraines. The first terminal moraine became Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, Block and Long Islands; the second terminal and lateral moraines formed the outline of glacial Cape Cod, surrounded by the rising sea level.

This blurry map shows the outline in green of glacial Cape Cod. You’ll note the outer Cape was much thicker, and did not extend to include Provincetown.

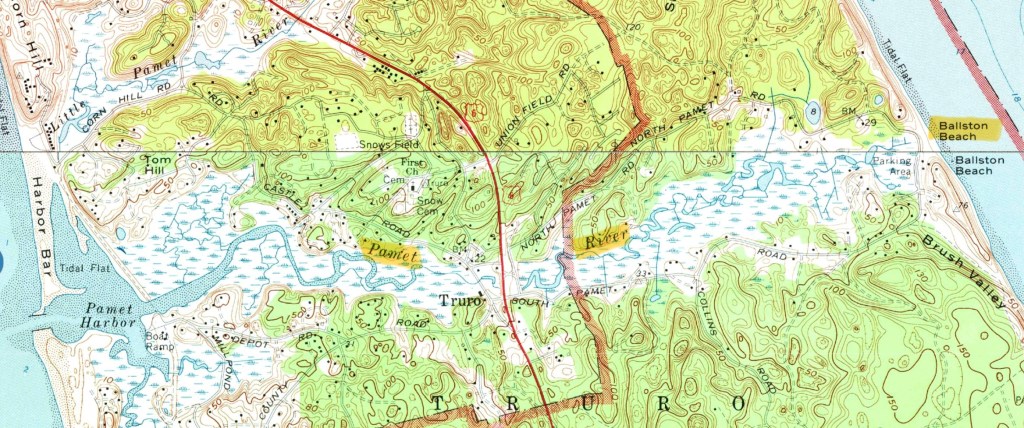

Wind and waves battered the Cape from the east, eroding the thick part and developing sand spits at the ends: Monomoy Island to the south, Provincetown to the north, which curled around. The erosion continues to this day, lighthouses and homes have had to be moved back, and the source of the Pamet River has washed away. Just like Mount Monadnock inspired the generic term monadnock for any isolated mountain not part of a range, the Pamet River gave rise to the term pamet for any river that has lost its source to erosion. This pamet has transected the entire Cape, which would have made the land north an island, had not the Army Corps of Engineers closed the gap at Ballston Beach.

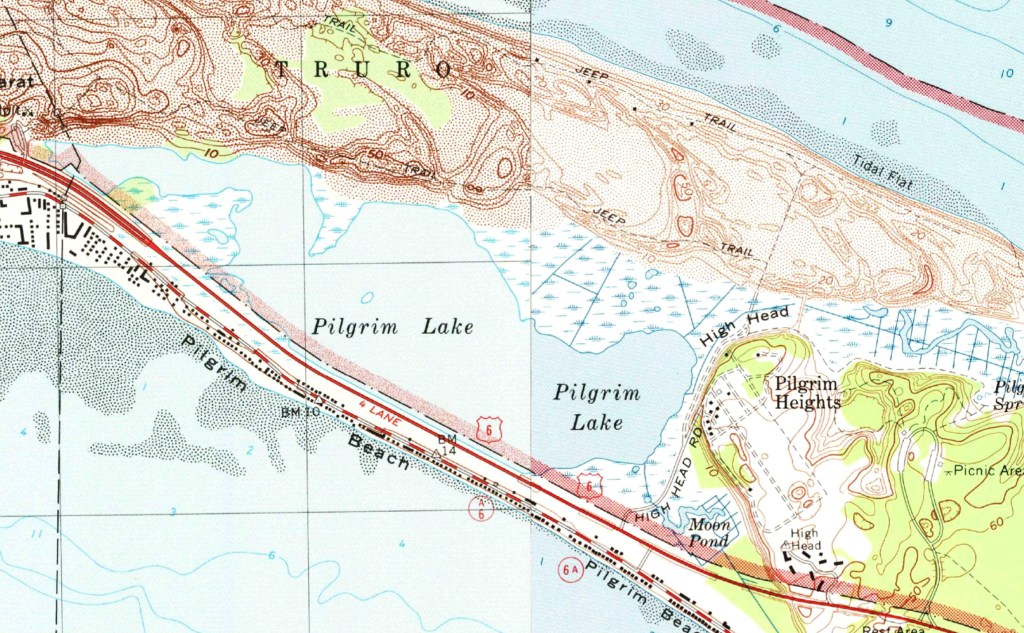

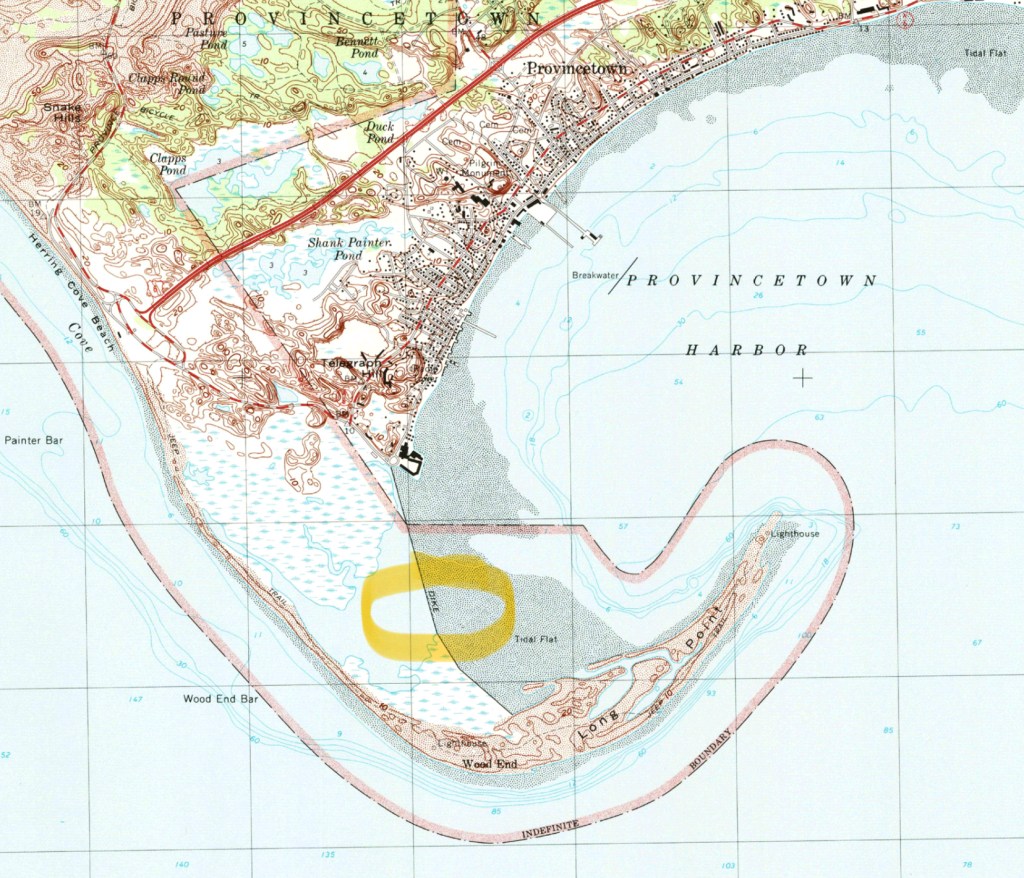

Let’s take a closer look at Provincetown. Glacial Cape Cod ended at High Head, everything beyond is sand spit

the first sand spit curled around and formed Pilgrim Lake

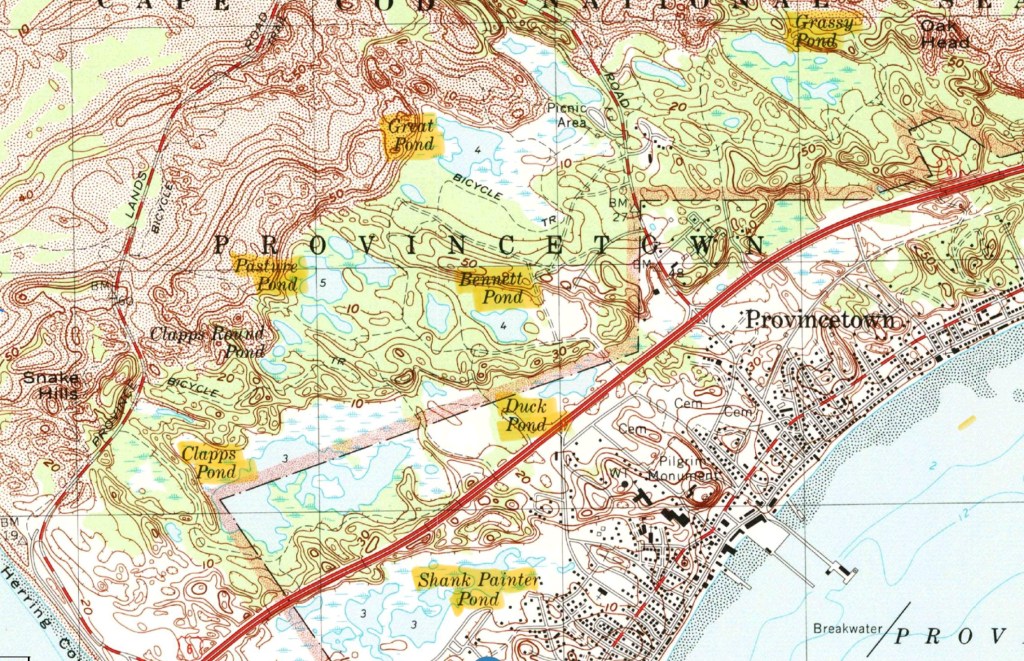

which was the first Provincetown Harbor. When that closed off, new sand spits grew, curled around and formed new Provincetown Harbors, closing off in turn and forming a chain of lakes.

The lakes show up better in this photo, Pilgrim Lake is on the right

The current sand spit (Long Point) would curl around too and form another lake, were it not for ongoing efforts to stabilize it, including a dike.

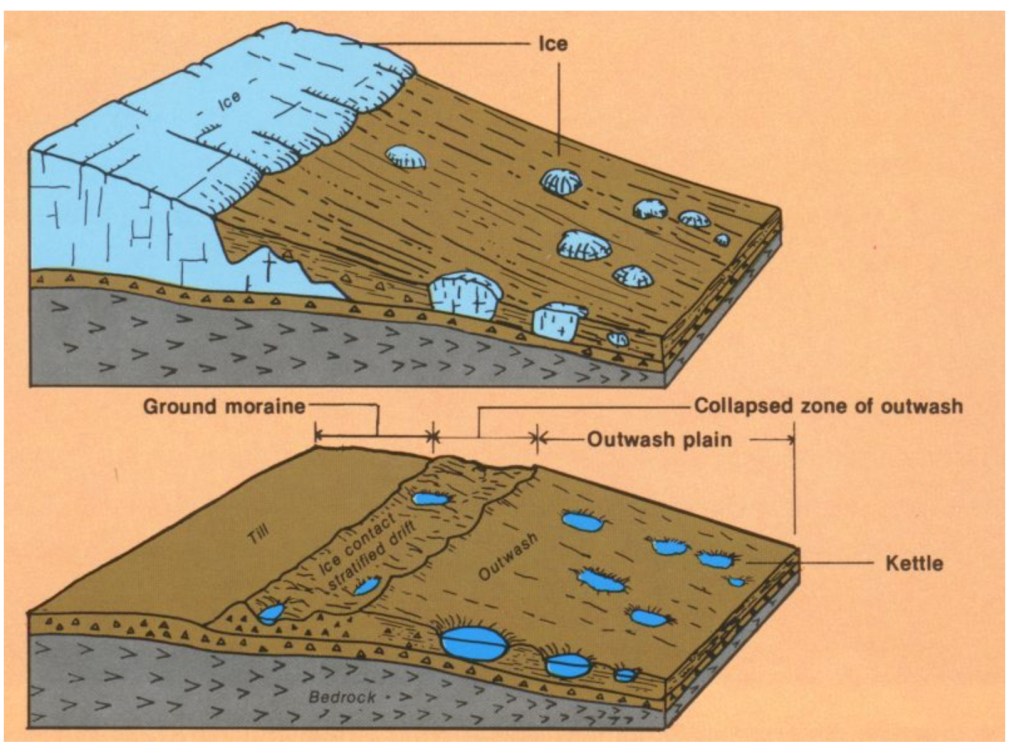

The lakes on glacial Cape Cod were formed differently. They are kettle ponds, caused by chunks of ice breaking off from the retreating ice sheet, leaving voids in the moraine and later filling with water.

The Cape is dotted with hundreds of these, and parts of it look like Swiss cheese.

Moraines, pamets, sand spits, kettles–and one more Cape quirk: erratics, which sound quirky all by themselves. I discovered these while trying to make a New England clambake for friends, where you make a big pit in the sand, line it with rocks, build a fire to heat them up, put the fire out, layer corn, clams, lobsters, and seaweed and cover with a tarp until the hot rocks thoroughly cook everything. The first step was to get a bunch of rocks, but I came up short. There are no rocks on the glacial Cape, just gravel and pebbles from the moraines. Only occasionally was a rock deposited by the receding glaciers, these were so rare they were called erratics. A stunning example is Doane Rock, near the visitor center in Eastham, the largest erratic on the Cape.

None of these quirks detract from the seminal feature of the Outer Cape, the Great Beach, over 40 miles of unbroken (except for a few breaches from storms) pristine strand facing the broad Atlantic. So different from the congestion and commercialization of the Inner Cape; we have JFK to thank for that. One of his last acts as senator was to sponsor the Cape Cod National Seashore, signed into law shortly after he became president. You can still find disgruntled old-timers who deplore his land grab, call him a communist, but most of us are very grateful.

Long ago the Great Beach was feared rather than revered, it represented a major navigation hazard. No rocks to threaten shipwrecks, the vessels simply got stuck in the shifting shoals and were stranded many yards from shore. If the crew braved the waves to reach dry land they often froze or starved to death on the desolate beach, with no facilities for many miles. Lifesaving stations were set up every five miles with regular patrols meeting each other to look for stranded ships, then launching rescues with Lyle guns to shoot ropes into the rigging and bringing the men to safety via breeches buoys. A few of these stations remain, they were the precursors of the Coast Guard. https://youtu.be/n-dEWCUJJrI?si=uVaiWwBqH-C6U4cw (skip ahead to 6:30 to see a Lyle gun rescue).

The opening of the Cape Cod Canal in 1916 allowed captains to bypass the Outer Cape, and render the lifesaving stations obsolete.

We moved away almost 4 decades ago, but that enigmatic spiral keeps calling us back, not a year goes by when we don’t visit. It’s been the destination of an annual bike ride, the subject of my next post.

©️ 2025 Scott Luria