Boston to Concord, Massachusetts. April 18–19, 2025, revised June 14, 2025.

My terrific high school history teacher, Brooke Miner, took pleasure in deconstructing American heroes. George Washington never chopped down that cherry tree, Andrew Jackson was a ruthless Indian killer, Abe Lincoln suspended habeas corpus, Teddy Roosevelt didn’t ride up San Juan Hill, Woodrow Wilson (for whom our high school was named) was a misogynistic racist. She had particular disdain for the Midnight Ride of Paul Revere: he never made it to Concord, never shouted “the British are coming”, was only a small cog in the network of people spreading the alarm that night.

Yeah, but the legend endures, the focus of much of Boston’s Freedom Trail. Longfellow’s great poem, embellished though it was, was based on fact and captured the spirit of the moment, the birth of a nation. America’s image has taken quite a hit lately, but at bottom I still believe we are the last best hope of earth.

I felt that back in 1975, when I and my college dormmates decided it would be a hoot to re-create the ride on its exact bicentennial. Fortified by beer and coffee, we rode our cheap 10 speeds without helmets or lights from the Old North Church to the Concord Battlefield. We were rewarded with an all night concert featuring Arlo Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Phil Ochs. It started to rain, and the six of us squeezed into a pup tent, surrounded by our bikes to keep from being trampled. At dawn we were shooed off the field to make way for the reenactment cannons and Gerald Ford’s speech.

Now, 50 years later, I felt compelled to repeat the ride. Another performative stunt, I suppose, but that seems to be my jam. Maybe it’s because I felt democracy is threatened, as it was 250 years ago, that it was time once again to spread the alarm. This time around, I have tried to research what really happened, compare it to the legend, and relive it in real time. I reached out to my dormmates, but suspect my emails went right to their spam folders. I had no better luck with my cycling buddies, who perhaps felt we were too old to be pulling all-nighters.

I looked for other mentions of the ride in popular culture, and found this song by Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers, told from the perspective of his horse, and much more factually accurate. https://youtu.be/ss038U9_8JA?si=RSPeXpJQKsAVgoUo

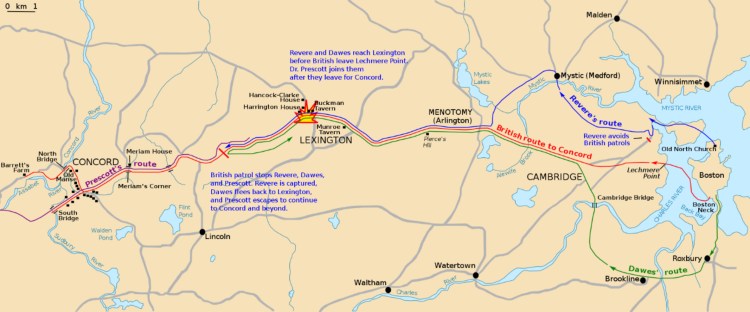

The National Park Service has a map that gives a good overview:

Right away, you can see that Revere wasn’t the only rider that night. William Dawes departed at the same time, taking the longer “land” route via Boston Neck. His unfair lack of recognition was lamented in an 1896 poem by Helen Moore.

At least Dawes got a little street cred, his hoof tracks through Harvard Square are preserved in bronze.

The mastermind behind these rides, this “alert,” was Joseph Warren*, a physician who was as active in the revolutionary cause as Samuel Adams and John Hancock. The latter two were visiting a cousin at the Hancock-Clarke house in Lexington, and Warren’s spies discovered the British commandant General Gage’s plan to arrest them and seize an ammunitions depot in Concord on the night of April 18, 1775. It was Warren who dispatched Revere and Dawes to warn Adams and Hancock and rouse the Minutemen, and who devised the “one if by land, two if by sea” signaling system at the Old North Church.

We should take a step back here to get the historical context. Why this “revolutionary cause?” Why the need to seize munitions? As I looked back from the present, I try to understand what was going on in the Massachusetts Bay area back then. The colonies had been content, the colonials proud to be Englishmen. What happened?

In the end, it was all about money. England was deep in debt from the Seven Years War, a.k.a. the French and Indian War. They had emerged victorious, conquered all of France’s holdings in North America, and reigned supreme as the greatest superpower on earth, but at a huge monetary cost. They took the national debt seriously back then. Since the war had been fought largely to protect the colonies from the French and the indigenous peoples, the king and Parliament thought they should share in the cost. The tax they levied was modest and reasonable, but was done without consulting the colonials first. This rankled the settlers, who felt their right to representation in governance dated back to the Magna Carta and the Mayflower Compact.

You probably know the progression—the Stamp Act, the boycotts, the Intolerable Acts, tarring and feathering of tax collectors, the Boston Massacre, the Tea tax, the Tea Party— a spiraling sequence of confrontations that resisted attempts at compromise and ultimately led to the declaration of martial law in Boston, the shutting down of local governments, and the occupation of the city by Redcoat regiments. The First Continental Congress in Philadelphia extended an Olive Branch Petition that was inexplicably ignored by the king. How could he have squandered a chance for a simple solution? There is evidence that he suffered from porphyria, a hematologic condition that can cloud the judgment cause frank psychosis, the “madness of King George.” Whatever, by that April night things were approaching the point of no return.

This April night I biked from my sister’s house in Newton to downtown Boston and followed the Freedom Trail to Paul Revere Mall and the Old North Church

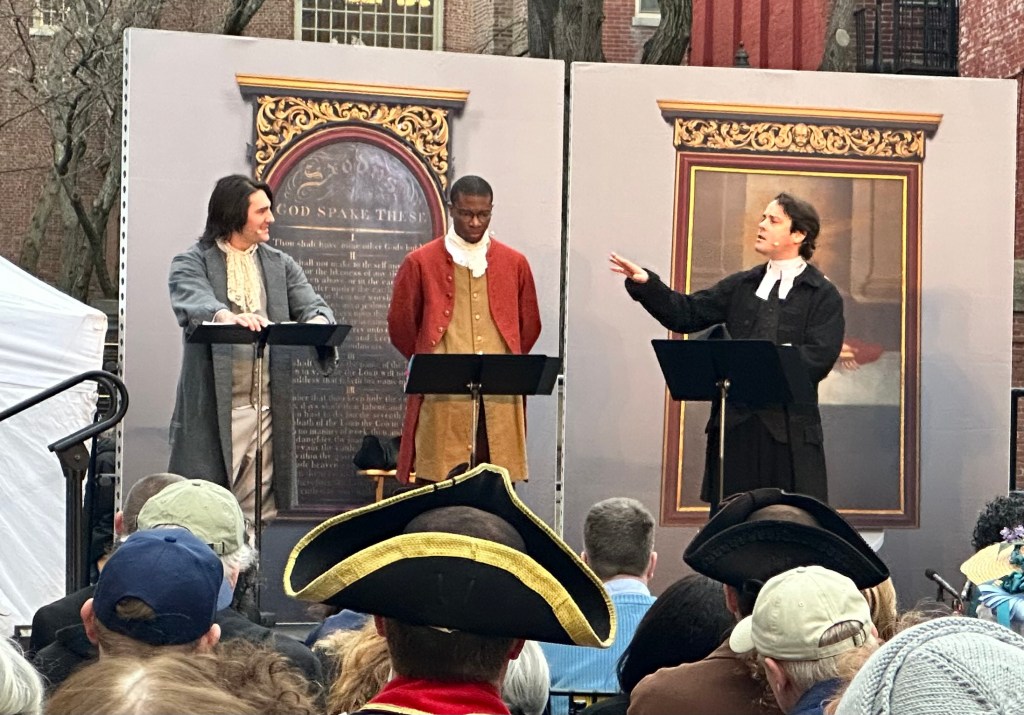

where the crowds were treated to a performance of Revolution’s Edge, a costumed play featuring a patriot, a loyalist, and a slave

followed by remarks from the mayor and the governor. Afterwards, we were invited to create our own paper lantern and join the procession following Revere’s route to the harbor, attend a special service witnessing the iconic two-lantern signal lighting the steeple

watch a dramatic reenactment of Revere’s crossing with music and a drone light show

And see Paul taking off down the streets of Charlestown

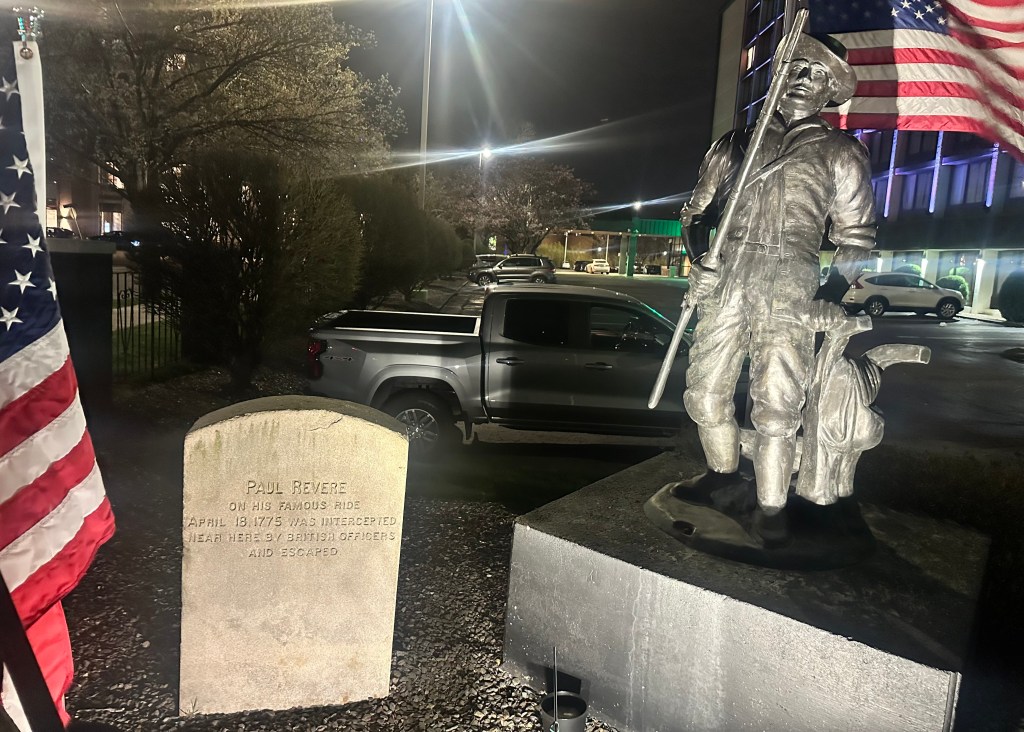

In Revere’s journal, he said he left around 11 PM, and after passing Charlestown Neck, turned left to head towards Cambridge and the main road to Lexington. But at a spot where “Mark hung in chains” (where a slave who had been executed 20 years before was still hanging, his decomposed corpse a grisly example) he encountered two Redcoat officers who gave chase; he had to backtrack and head for Medford instead, barely eluding capture. I found a monument marking the spot in front of a Holiday Inn.

He never yelled “the British are coming” since everyone considered themselves British, and shouting would have attracted the attention of the patrolling sentries. Instead, he stopped at houses and warned the occupants quietly. I followed in his wake, dodging the late night traffic, and stopping at the home of Isaac Hall, captain of the Medford Middlemen, which is now an Islamic cultural center.

He reached the Clarke house in Lexington in the early morning, and warned John Hancock and Samuel Adams that soldiers were coming to arrest him.

The reenactors arrived at the Clarke house ahead of “schedule”, 10:30 PM. I got there at 12:30, closer to the actual time, the crowds were all gone.

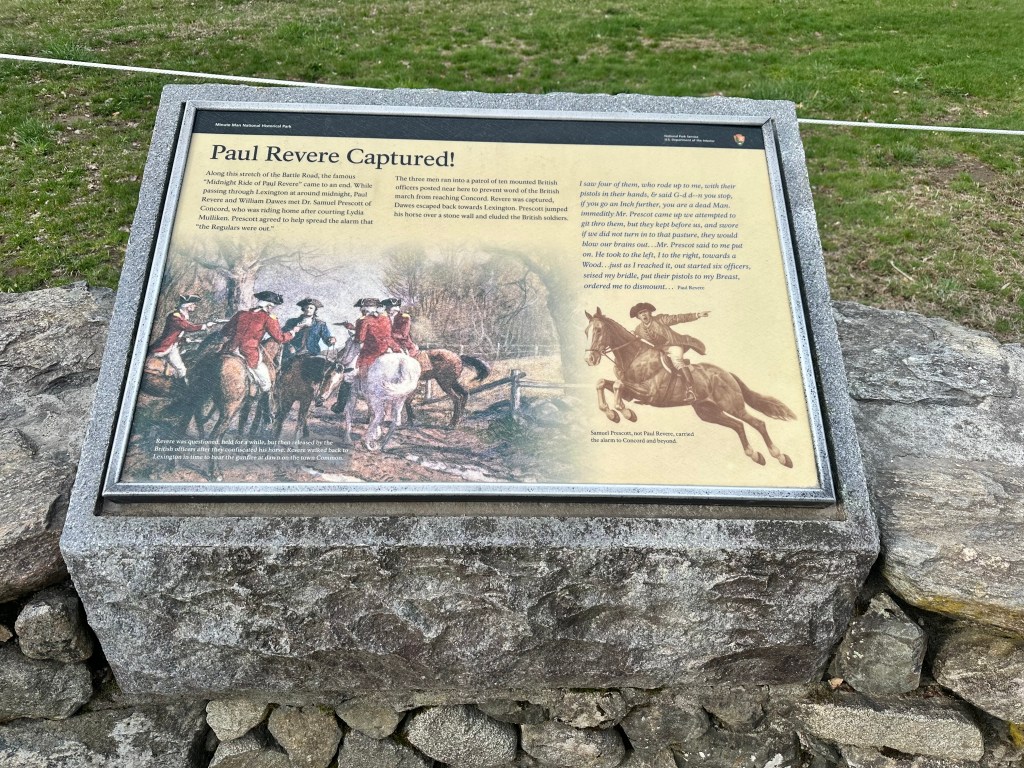

Revere and Dawes rode on towards Concord, but were intercepted by British soldiers a couple of miles down the road, Revere was captured, Dawes turned around, but a third rider, Dr. Samuel Prescott, who had joined the group after making a scandalous late night visit to his lady friend in Lexington, managed to elude the soldiers by jumping over a stone wall, and made it to Concord. So the famous Midnight Ride was completed by a Lothario.

I decided to stick around and watch the reenactment at Lexington, they have one every year, but this was supposed to be the most elaborate ever. It began at 5:15 AM, but they said to arrive a couple of hours early to have any chance of getting a spot where you could see. Sure enough, by 1 AM there were already a couple of hundred people clustered around the viewing area, many with sleeping bags or lawn chairs. I had nothing but a 1-foot square “butt pad” and settled down against a tree, just like Rip van Winkle did all those years ago. He caught a lot more than 40 winks, woke up to find he had missed the entire American Revolution; I was hoping to just get a couple of winks.

It was not to be. The crowd steadily filled in around me, kept tripping over my legs, and a very knowledgeable reenactor stopped by the barricade, and gave an excellent history lesson— with the result I got no sleep at all.

If the Revolutionary War, if “America” had a starting point, it was at Lexington. It’s not that simple of course, but John Parker’s words resonate: “Stand your ground. Don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” I passed his heroic statue at the apex of the green on the way to my “resting place.”

The statue often confused with the “Concord Minuteman” statue at the Old North Bridge (which I’ll be visiting later this morning) by Daniel Chester French, who also sculpted Lincoln at the Memorial, and John Harvard in the Yard.

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Concord Hymn appears below it, with the famous line “the shot heard around the world.” But where was that shot? There was certainly gunfire hours earlier, in Lexington. Who fired it?

I read and researched extensively before my little ride, and was gratified to see the reenactment was as historically accurate as I could determine. Certainly worth waiting for. As I rose on my aching bones from under that tree, there were five packed rows ahead of me, and many thousands crowded around the green, with Jumbotrons erected for the people in back. My height counted for something, and I tried to take a video, but the woman in front of me kept hoisting her child on her shoulders. This clip from YouTube shows it much better anyway. https://youtu.be/Rgl49Wkkz4E?si=bREGcqOExD9s4j5E It’s quite long and worth watching in its entirety, but the main action begins at 7:30 when the mysterious first shot rings out, followed by panicked general fire on both sides, with the British officers desperately trying to control their men who were running amok. Equally compelling was 10:30, when the officers realized the countryside had been alerted, the mission had been compromised, and that they should go back to Boston. They were overruled by their commander, with devastating consequences.

When the smoke cleared, there were eight Colonials dead.

The battle was immortalized in the song “Mama Look Sharp” from the musical 1776. I can’t listen to it without misting up. The YouTube clip omits the preamble:

You seen any fighting?

Sure did. I seen my two best friends get shot dead on the very same day. And at Lexington it was, too. Right on the village green.

When they didn’t come home for supper, their mamas went down the hill looking for them. Mrs. Lowell, she found Timothy….right off.

But Mrs. Pickett, she looked near half the night for William. He went and crawled off the green…before he died.

By now I was running on fumes, but pushed on to Concord, passing the Paul Revere capture site

the reenactment at the Old North Bridge, less well done than at Lexington

No rock concert this time, and no way was Trump going to show up in this deep blue state.

The battle at Concord was kind of a draw. The alerted villagers had moved their ammunition stockpile, the British could only find a few weapons and set those on fire, the militias in the hills beyond saw the smoke, thought the troops were burning their town, and advanced across the bridge. Losses were fairly light on both sides, but the British decided to withdraw.

That withdrawal, the least-known part of the battle, was where most of the casualties occurred. Retracing their steps along the “Battle Road” preserved as Minuteman National Historic Park, the Redcoats were continuously harassed by the enraged colonials, whose numbers had swelled to many thousands, firing from behind trees and stone walls, guerrilla warfare really. The British were equally furious, they had started their mission soaking wet after disembarking from their boats in a swamp, had marched 20 miles and having failed in their objective had to retreat 20 more under unrelenting fire, which they felt was cowardly, their opponents not coming out into the open. Their losses on a hill dubbed Parker’s Revenge were particularly devastating. Emblematic of their fury was there treatment of an 80-year-old resident of Menotomy (now Arlington).

When all was said and done, the British expedition, designed to discipline the upstart provincials and show them who was boss, had the opposite effect, and sent the country down the road to independence. The numbers tell the tale.

My expedition was a lot less traumatic.

- * Joseph Warren was killed in the Battle of Bunker Hill, as you will see in my next post. His younger brother was a founder of Harvard Medical School, and his nephew helped to start Mass General Hospital, which has a building named in his honor.

Scott- another fabulous post & a very fun ride for you. Best of luck!

LikeLike

Great research Scott and appreciate the details and the historical context!

LikeLike