Dillon to Georgetown, Colorado, Saturday, July 13, 2024.

You boomers out there might remember the Truckers/CB radio craze of the 1970s, that added phrases like “Breaker one nine” and “10-4, good buddy” to the cultural lexicon. Much of it was inspired by the CW McCall hit Convoy, later made into a Sam Peckinpah movie, followed by The Burt Reynolds/Sally Field vehicle Smokey and the Bandit. The craze lionized long-distance truckers as modern-day cowboys, cackling to one another over their CB radios and harassed by overzealous state troopers they called Smokey Bears or Smokies.

Well before there was Convoy there was Wolf Creek Pass, CW McCall’s other hit, a hilarious story of a truck full of chickens crossing the continental divide and careening down the other side out of control. It’s worth a listen. https://youtu.be/KHb_0Lhegig?si=3MhruoAXTFgP38G9

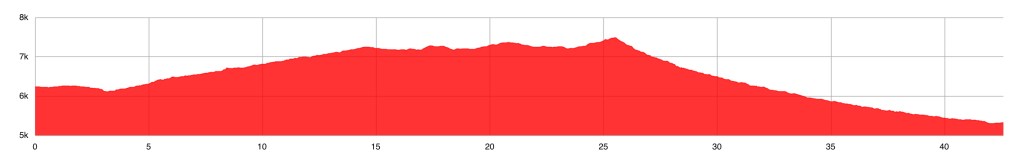

So Loveland Pass was going to be my fifth and final crossing of the great divide. You may remember when I was being blown east on I-90, following the Yellowstone River in Montana, that I felt I was home free, through the Rockies, and could just head back to the east. But no, I had to turn back, cross the divide four more times, and visit those other highpoint parking lots. Now, finally, I’ll be free, through the Front Range of the Rockies, able to go home.

I’ve done this pass before, in 2009, while picking off fourteeners, and it didn’t seem so bad, but I was 15 years younger and both me and the bike were lighter. I was approaching the beginning of the climb in Keystone, when I was dismayed by a flashing highway sign: “Loveland Pass closed for event.”

What? This was the first I heard. I had even asked a policeman in Dillon if there was any problem with biking over the pass, and he said it should be fine. But the event guard said no, this sign has been flashing for days, he could let me by for now, but I would probably be stopped further up.

The event was the Triple Bypass https://www.triplebypass.org, a huge ride with 4,500 cyclists going over three major Colorado passes, for a total of 110 miles and 10,800 feet of climbing in a single day. One of the biggest events in the country, and, like Hood to Coast, one I’d never heard of. They’d all started at sunrise, and were coming in my direction, Loveland was their second pass. I pedaled on with dread, waiting for the police to pull me over, wondering what I do with my nonrefundable reservations and friends who were expecting me.

But nobody stopped me. It was wild, cranking or walking slowly up that huge hill, with an endless stream of ultra-fit cyclists whizzing down, many shouting words of encouragement to me like “You’re a beast!” or “Superhuman!” I waved gaily at them, but thought, yeah right. An old fat guy pushing his overloaded bike up the hill.

Unlike at Independence Pass, there was a food stop halfway up, a nice outdoor café at the foot of Arapahoe Basin, which has the highest in-bounds skiable terrain in North America.

I was seated in the hot sun, but a gentleman motioned me over to share his shaded table, and he turned out to be a fellow physician. Mark was a family practitioner in southern Colorado who was here for a conference at Keystone. I hadn’t spoken to another doctor in months. A wonderful break.

The last 4 miles to the top of the pass were the steepest, and I wound up walking most of it. I didn’t mind, it was fun to watch thousands of cyclists racing down the hill, the car traffic was limited to occasional boluses, led by a police car. I had to keep reminding myself to look behind me, to see the beautiful valley I was coming up.

I can’t count the number of times cars slowed down and asked if I needed any help. I did encounter a cyclist who had a serious breakdown, his derailleur hanger had broken off, and he had broken a couple of spokes. I have a lot of tools, but I couldn’t help him with that, he was waiting for a sag wagon.

Reaching the crest was a solemn moment for me. This was the shoulder of the last giant, the lip of the Front Range, the final crossing of our country’s spine. Denver, the Great Plains, and the Atlantic Ocean lay below.

CW McCall’s song rang through my ears as I flew down the other side, glad I wasn’t carrying any chickens. Weird to feel the potential energy I’d stored up in the seven days of climbing since Glenwood Springs released as kinetic energy, miles and miles of endless downhill. Denver was almost 7,000 feet below. I rejoined I-70 just as it was emerging from the Eisenhower Tunnel. 15 years ago I’d had to ride on its shoulder, but now there was a bike path and I could relax and really enjoy the dazzling scenery. I was now following the boiling rapids of Clear Creek, a tributary of the South Platte. Georgetown was a historic mining town, and a restored steam engine was offering rides.

But I was happy with a smash burger at another outdoor café, and a snug motel room after a long day.

Distance 33 miles, 3,037 total. Time 10 hours with stops. Elevation gain 3,520 feet

©️ 2024 Scott Luria