Idaho Falls to Ashton, Idaho. Tuesday, June 11, 2024

OK, I’m not proud of this. After yesterday‘s wonderful–but–grueling day, I just decided to just let the wind blow me up US 20, rather than taking a longer bike route, which would’ve shown me more of the back roads. Much of it was a limited-access highway, but those are legal for bicycles in Idaho and 10 other states. Although traffic was heavy, there was an excellent shoulder all the way, I just had to be careful about off-ramps and on-ramps. The result is not many interesting stories or pictures.

There was one picture I was hoping to get. I have never seen the back side of the Tetons. The front side, the view from Jackson Hole, is legendary and changed my life. I remember the day, August 20, 1970–we were on the stereotypical “family trip out west” with a pop-up camper in tow. Up until that day, I was indifferent about mountains. I had been forced to hike a few in summer camp and came to dread the experience. This was mitigated somewhat when Glenn T. Seaborg took me on my first hike up Old Rag Mountain in Shenandoah National Park, but I was still unconvinced.

On that day, we crested Togwotee Pass, and got our first eye popping view of the Tetons.

And in that instant, I was hooked on mountains. I looked up the geology:

Between six and nine million years ago, stretching and thinning of the earth’s crust caused movement along the Teton fault. The west block along the fault line rose to form the Teton Range, creating the youngest mountain range in the Rocky Mountains. The fault’s east block fell to form the valley called Jackson Hole. This simultaneous rising and falling created a range that sprang 7,000 feet above the valley floor with no foothills. There are higher mountains in the Rockies, but none as spectacular.

I was obsessed. I had to climb the highest one, the Grand Teton. Seven years later, just before medical school, I signed up with the Exum guide service and did just that. You spent two days learning the basics of rock climbing and rappelling, then hiked up to a camp at the base of the Grand, and did the actual rock climb early the next morning. As is the tradition for western peaks, you were on the summit by 7 AM. I have great slides of that trip, and will look into getting them transferred to this blog. I remember the simultaneous thrill and disappointment of being on the summit. This was the second highest peak in Wyoming; Gannett Peak in the Wind River Range, was 34 feet higher. It would be 40 years before I summitted that one, after three failed attempts. More on that later.

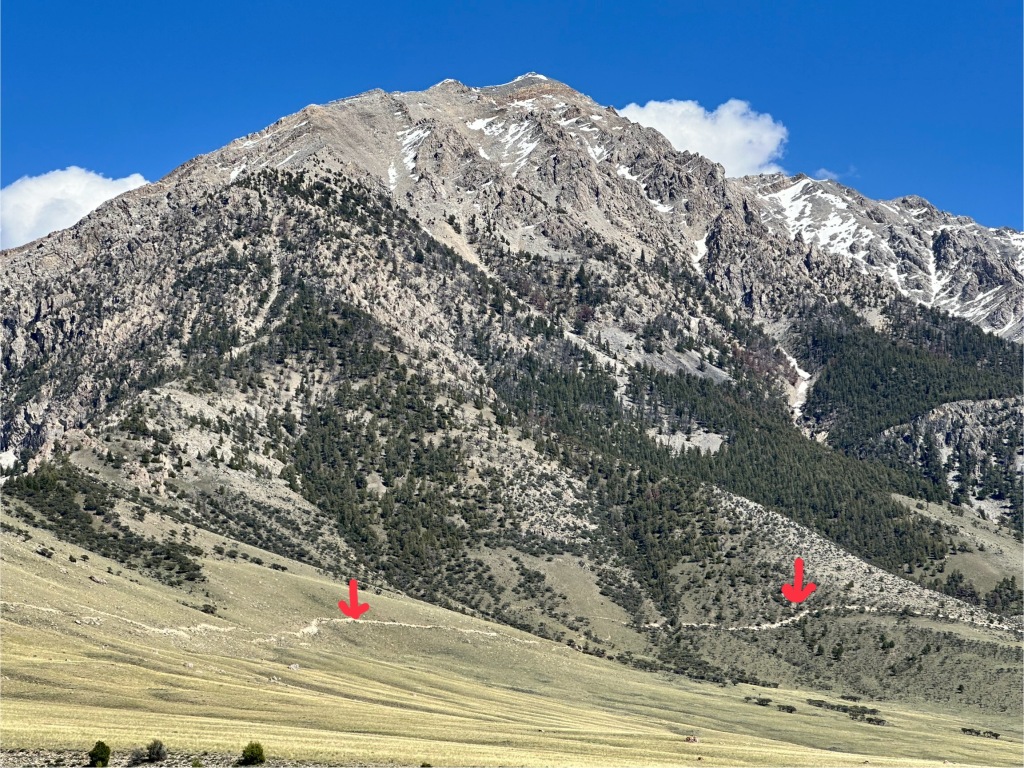

Anyway, I always wondered how the Tetons would look from the other side, the side that didn’t have that benefit of the sudden rise. This was the best picture I could get today—less dramatic than I hoped, not much contrast between the gray peaks 40 miles away and the dull blue sky. Not bad, but a little underwhelming.

This was the view that inspired early French trappers to give the range its name, Les Trois Tetons, the three breasts. I guess they’d been away from home a while.

Anyway, that’s all I have to report. Hope to make West Yellowstone tomorrow.

Addendum: I just edited this post to change backside to back side. Otherwise, my post about Tetons and backsides sounds like T & A.

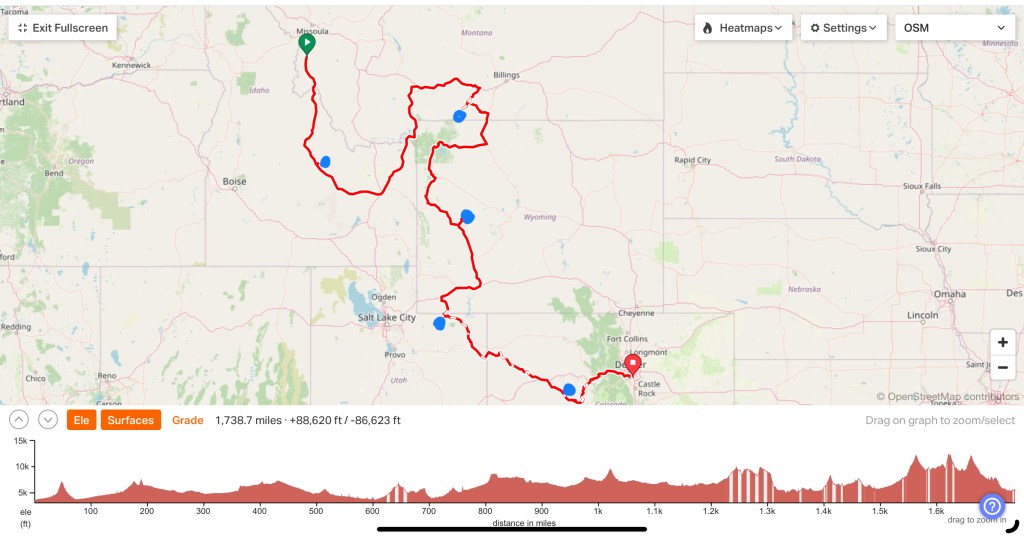

Distance 54 miles, 1,678 total. Time 7 hours with stops. Elevation gain 743 feet

©️ 2024 Scott Luria